It’s Halloween, which means creepiness is in season.

In many ways, though, creepy season spans the calendar: horror, science fiction, fantasy and other genres that frequently make use of Gothic motifs are bigger than ever. On television, in particular, shows like American Horror Story, Hannibal and others double down on their uncanny chills and thrills.

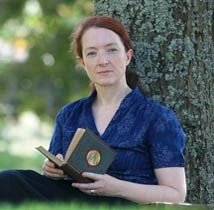

Julia Wright, Professor of English at Dalhousie, has been keeping her eye on Gothic television for some time now. Dr. Wright, who delivered this week’s Know Your Dal lecture, is the author of the forthcoming book Men With Stakes: Masculinity and the Gothic in US Television. The book looks at various television series over the past 20 years, including Supernatural, Angel, Millennium and others.

Julia Wright, Professor of English at Dalhousie, has been keeping her eye on Gothic television for some time now. Dr. Wright, who delivered this week’s Know Your Dal lecture, is the author of the forthcoming book Men With Stakes: Masculinity and the Gothic in US Television. The book looks at various television series over the past 20 years, including Supernatural, Angel, Millennium and others.

Scaring with style

The Gothic — which Dr. Wright defines as the use of supernatural devices and/or unusual and gloomy settings to establish a sense of dread — dates back to the 18th century and remains popular through the present. Classic Gothic works include such iconic texts as Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Rather than being a form in and of itself, it spans literary and other narrative forms.

“The Gothic is more about style,” she explains. “It’s about elements that can appear in one page of a text that’s otherwise realist or comic or what have you.”

Part of the Gothic’s power is its leveraging of what Sigmund Freud called “the uncanny”: when something that is familiar but still strange, or “not quite right,” leading to a sense of dread and uncertainty. Another reason for the Gothic’s enduring appeal is its ability to serve as a metaphor for social, economic and political anxieties.

“In broad terms, supernatural powers commonly mark a concern about powerlessness,” says Dr. Wright, noting, as an example, how most classic vampire characters are aristocrats who “feed” on the lower classes. “Social powerlessness gets expressed through someone who has this surreal, excessive power.”

Architecture and anxiety

Dr. Wright’s lecture focused on two particular common trends in Gothic literature that often find their way into Gothic television, both reflecting anxieties of and threats to middle-class lifestyles. The first is the “Angel in the House,” a theme immortalized in a long poem of the same name by Coventry Patmore. The motif idealizes the middle-class woman as docile, selflessly devoted to her husband and family, without an inner life or interests beyond them — and the outside world is constantly a threat.

This “angel” role has often been associated with the name “Lucy” (including in Dracula). The TV series Millennium, which ran from 1996 to 1999 under the watch of X-Files creator Chris Carter, flipped the narrative by creating a murderer named Lucy that could switch gender and who, in the episode “Lamentation,” murders a friend of protagonist Frank Black in the basement of the show’s iconic yellow house. Dr. Wright points out that the house is shot in a particularly twisted way: “They tilt the shot until the angles get weird to generate Freud’s sense of the uncanny.”

The houses themselves also play a key role in Gothic stories, including many cases of “houses that don’t quite fit.” Dr. Wright describes how houses in nineteenth-century Irish literature often served as metaphors for colonization, for the stranger who now rules the land. One modern example she points to is the early episode of the popular CW series Supernatural, titled “Bugs,” where swarms of bugs are killing those involved in a new housing development on land with a troubling colonial past.

“The house that doesn’t fit, the house that has the wrong angles, the house that’s built on the dead, suggests that something is not right, and suggests we need to set our social house in order,” says Dr. Wright.

Dr. Wright’s book Men With Stakes will be released by Manchester University Press in early 2016.