News

» Go to news mainThere's Something in the Water

Dr. Ingrid Waldron launches There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities

On Wednesday evening at the Halifax Central Library’s Paul O’Regan Hall, Dalhousie University’s Dr. Ingrid Waldron (associate professor in the School of Nursing and Department of Psychiatry) and several community activists informed and inspired a crowd during her pop-up book launch for There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities (Fernwood Publishing).

Dr. Waldron’s approach to this event, inviting the book’s subjects to read excerpts then share their stories in their own words, was the perfect demonstration of the value of this kind of community-based research. Each passage was rich with detail about a specific struggle against environmental racism. At the legislative level, Dr. Waldron has worked with NDP MLA Lenore Zann to introduce an act to prevent environmental racism, which has been through various iterations and sparked groundbreaking debate at Province House on this topic.

At the community level, each individual’s story touched the hearts of those in attendance, and showed that resilience, perseverance and knowledge (of one’s history and rights) can eventually win out.

And the academic speakers—Dr. Waldron, Dr. Ellen Sweeney (Dalhousie MA Anthropology, 2006), and Dr. Mikiko Terashima from Dalhousie’s School of Planning, Department of Community Health and Epidemiology—synthesized and contextualized the grassroots, community knowledge, giving it even more power.

Dr. Waldron spoke of the multiple objectives in writing her book: to conduct a deep and thorough examination of environmental racism through research; to focus on race with an environmental lens that is broader than conservation and sustainable development; to document the “impacts on spirits, minds, and bodies” of the disproportionate exposure to toxins among Mi’kmaq and African-Nova Scotians, especially women.

“There is a dearth of studies on environmental racism in Canada,” she noted. The power in her work is “grounded in and evolved out of community members,” meaning that their interests and needs have driven the research. Dr. Waldron wants “divergent voices to resonate throughout my work.”

The evening’s speakers collectively showed the multi-generational impacts of environmental racism, each highlighting the experience of a specific community:

Africville

Irvine Carvery spoke of growing up in Africville, an African-Nova Scotian community where, before evicting residents and razing the community completely, for decades the city sited undesirable features like the city dump in the 1950s.

Other sites, Carvery said, were considered but “all dismissed because of health concerns.” Industrial, residential, hospital, and municipal waste were dumped 300 metres from the community. “My oldest brother was killed by a truck going to the dump,” he said, and “three people died from poison at the dump.” An investigation found the producers and dumpers of the poison not responsible. “They blamed the victims for their own deaths,” because the bylaw said they weren’t allowed to be there. Carvery also spoke of psychological trauma due to his fear of fire in the community, because dump fires were commonplace.

In 2011 tests found residues of toxins still at the site five decades after it was razed. “We had no political power, no economic power ... The impact of that is still present today.”

Elsipogtog

Michelle Paul’s message about the Mi’kmaq defense against Southwest Energy (SWN), a Texas-based corporation that wanted to frack for natural gas “directly beneath the reserve,” might best be summarized in her statement: “We asserted treaty and we won.”

She made a clear distinction between the terms “protestors” and “protectors.” The Mi’kmaq and their allies were not protesting anything, she said to rousing applause. They were defending the land, the water, and their rights.

She was also humble in sharing credit with allies like the Acadian community and organizations like the Ecology Action Centre and the Council of Canadians. “The coming together of community is what caused the victory.”

Her words once again echoed the power of Dr. Waldron’s work, making broader connections among communities for a greater purpose. As Paul put it: “The power is in the people not the people in power.”

Shelburne’s Black Loyalist Community

“For over 50 years they dumped their garbage in my community,” said Louise Delisle of the South End Environmental Injustice Society, an organization based in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, a community founded by Black Loyalists in the late 1700s. “Less than 30 metres from our home.”

She noted how her own story was reminiscent of the Africville experience with the Halifax dump, and several other African-Nova Scotian communities where dumps were placed. Delisle noted that it seems like “every day there’s somebody being diagnosed with cancer,” and that many in the community suffer chronic coughs due to the smoke from constant dump fires.

“My father would always have us ready to go,” she said, in case it spread. Her mother would check the children’s beds for rats before bedtime. “We weren’t second-class citizens,” she said. “We were lower.”

Delisle expressed gratitude to Dr. Waldron’s ENRICH—Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities & Community Health—project, which she said “gave us the opportunity to name what was happening to us: environmental racism.” But she said while the name was new, the concept was not. It’s the same racism.

In 2016, Nova Scotia Environment found an oil spill had occurred within the dump. The community is now working with ENRICH to establish a database linking the dump with community health concerns.

Brine Dumping in the Sipekne’katik River

Dorene Bernard, a “Mi’kmaw Grassroots Grandmother,” told her story of Mi’kmaq defenders of the Sipekne’katik (Shubenacadie) River. Alton Natural Gas wants to use water from the river in a pipeline 12 kilometres away, she said, then dump the brine back into the river, but has not properly sought consent from the Mi’kmaq.

“Mi’kmaq treaty rights have never been consulted,” she said, for any of the major energy projects with significant environmental impact, including offshore oil exploration.

“It is our responsibility as women to protect the water, to protect the land.” She added that the Mi’kmaq were not given sufficient time to review the environmental impacts of the project. In fact, they only found out about it in 2014 by investigating pipes being placed at a clear cut visible from the highway.

After winning a provincial Supreme Court decision against Alton in 2017, Bernard reported that “today we’re at a stalemate.” She noted the ongoing challenge for the Mi’kmaq of dealing with governments that have significantly different worldviews from their own. While governments list species at risk, for example, Bernard notes that with current treatment of the environment, “we are all at risk.”

Mapping Environmental Racism

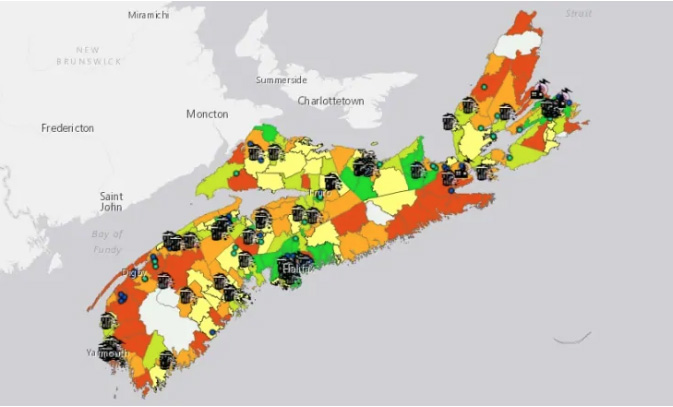

Dr. Mikiko Terashima from Dalhousie’s School of Planning tied many threads together in her discussion of the ENRICH online map at enrichproject.org, which maps out communities in Nova Scotia that are close to environmental hazards. The map, while not definitive, gives some indication that these tend to be sited near Mi’kmaq and African-Nova Scotian communities.

The map, Dr. Waldron noted in the book, is one of several tools to support communities in approaching governments arguing the legitimacy of their claims.

“I appreciate the power of maps,” Dr. Terashima said. In particular, this one has two salient features. Anyone can interact with it, and it is based on community inputs. “It is data that that no government or academics have … It demonstrates the potential for true partnership.”

Inspirational storytelling and well researched facts make a compelling case, not just regarding the problems people face, but also about the work communities are doing to assert their rights and to protect Nova Scotians against environmental racism.

Learn More:

Recent News

- Bridging continents: Dal students to learn, share and connect in West Africa

- Partnership between UpLift and Public Health sees continued funding allocated for Youth Engagement Coordinators

- Dal Health grad students use podcasting to discover the people behind the science

- Nursing student closer to living out her dream of helping people thanks to support of new award

- Master of Nursing grad passionate about working in mental health and addictions

- MSc Audiology grad shifts career from entomologist to audiologist

- Occupational Science grad exploring concept of care farming

- Dal Crossroads continues 20 year legacy of student ‑led learning