It’s a new celebration for the “New Dawn” of Dalhousie’s third century.

Dalhousie unveiled its eagerly anticipated ceremonial object Friday, May 10 in Truro, with the New Dawn Staff of Place and Belonging taking its place on stage during the first Spring Convocation ceremony of 2019.

With the introduction of the symbolic walking stick, revealed with a tug on a piece of black linen under which it was hidden, Dal became one of the first universities in North America to retire its traditional mace in favour of a new ceremonial object.

“With today’s unveiling, the New Dawn Staff of Place and Belonging now officially replaces the university mace as the ceremonial object used to open and close all Convocation ceremonies,” said Dal’s Interim President Peter MacKinnon in remarks at the ceremony.

The Staff was designed and crafted specifically for Dal by artists Alan Syliboy of Millbrook First Nation and Mark Austin of Colchester County (pictured with the Staff), with guidance from the university and in collaboration with a team of artists and craftspeople from diverse communities across Nova Scotia. Wendie Poitras, Annie Martin, Mohammed Issa, Jessie Marshall, Mark Hamilton, Matt D'Entremont, Fred Marshall, Lily Volio, Debby Finkbeiner, and Arjun Lal all had a hand in bringing the Staff to life.

The Staff was designed and crafted specifically for Dal by artists Alan Syliboy of Millbrook First Nation and Mark Austin of Colchester County (pictured with the Staff), with guidance from the university and in collaboration with a team of artists and craftspeople from diverse communities across Nova Scotia. Wendie Poitras, Annie Martin, Mohammed Issa, Jessie Marshall, Mark Hamilton, Matt D'Entremont, Fred Marshall, Lily Volio, Debby Finkbeiner, and Arjun Lal all had a hand in bringing the Staff to life.

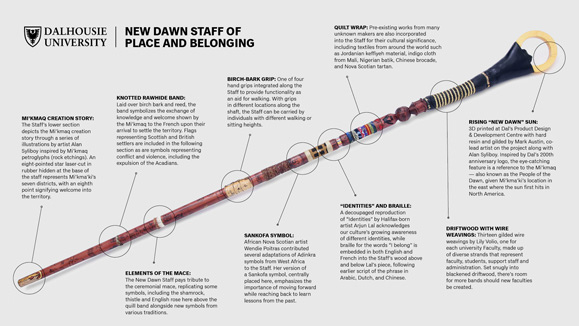

At 7’4” (2.24 metres) tall and with dozens of symbols and materials integrated along the shaft, the Staff cuts an impressive figure befitting of a symbol of achievement. It’s also a powerful metaphor for a journey, educational and otherwise.

“The Staff functions to support the person holding it just as the university community is there to help support the dreams of our students throughout their academic journey,” says Professor Kevin Hewitt, chair of Dalhousie’s Senate, which unanimously approved the staff as the university’s new ceremonial object at its meeting in late April.

Dr. Hewitt was a member of the Mace Re-Think/Re-Vision Committee established in 2016 as part of the university’s Strategic Initiative on Diversity and Inclusiveness. The committee identified and led the development of the new object with the aim of better reflecting the current diversity of the Dal community and its values, while still paying tribute to the university’s history and heritage.

Senate’s unanimous approval — which came exactly three years and one day after the committee’s kick-off meeting, and with a standing ovation for the artists on hand to present it — was a powerful endorsement for the New Dawn Staff and what it stands for.

“It seems to be the entire institution is moving forward, and the standing ovation was symbolic of that,” says Dr. Hewitt.

A history lesson and more

To see the New Dawn Staff from afar is to behold an object that is at once commanding of respect and attention, yet also welcoming in its appearance. A gilded arc-shaped sun rising out of coal-stained driftwood at the top catches the eye immediately.

Up close with the New Dawn Staff of Place and Belonging (click to enlarge)

But it’s when you zoom in on the base of the Staff that the story really begins. That’s where a laser-cut rubber replica of a Mi’kmaq petroglyph — an eight-pointed star based on the original rock etching found near Halifax — is fused onto the Staff.

Circular in shape, the petroglyph reflects a vision of life itself as an action of continuity, with seven of the points representing the different districts of Mi’kma’ki and an eighth signifying the welcoming of others into the region. Although hidden from direct view, it’s one of the Staff’s most important symbolic design features. That’s because when the Staff is in use, the tip touches the very ground that it is meant to represent—the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq upon which Dalhousie sits.

The bottom tip of the Staff, with petroglyph.

That tip and the collection of symbols featured on the lower segment of the Staff represent the Mi’kmaw creation story and are the work of Syliboy. Elsewhere in the section there’s a vulva representing Mother Earth; a folded quill star with four colours and four directions signifying inclusion; stars for wayfinding; male, female and 2-spirited figures; a gilded Grandfather Sun that mirrors the arc at the top of the staff and more. Farther up the Staff, Syliboy has drawn a turtle to represent Turtle Island, an Indigenous name for North America.

These designs, wood-burned by Mi’kmaw artist Annie Martin, and natural materials integrated along the shaft signify Dalhousie’s location in Mi’kma’ki and important on-going relationships with Mi’kmaq communities.

There’s a similar depth and richness in detail carried throughout the entire Staff. The symbols are arranged bottom-to-top in loose chronological order, with several sections marking major historical developments, from the waves of European settlement and the conflicts and eventual peace that followed to the arrival of greater numbers of peoples of African descent forced here through enslavement or an attempt to escape it. Closer to the top, the Staff takes on a different tenor, with elements reflecting the aspirational pathways of students, faculty and others at Dalhousie today.

From revised mace to uncharted territory

The project originally began as an initiative to update the university mace but evolved into a discussion of what a new ceremonial object could represent and how it could fit into the contemporary university environment and at Convocation.

“We had the blessing of the university to do something courageous and try to rethink what could replace the colonial tradition that the mace represented, and that spirit was there from senior administration on down,” says Peter Dykhuis, director and curator of the Dalhousie Art Gallery and chair of the Mace Re-Think/Re-Vision Committee.

While the Staff serves as a history lesson of sorts, it is not meant to be exhaustive in this regard or strictly linear, says Austin. The unique mix of symbols, materials and textures is meant to reflect the rich diversity of individuals who make up the Dalhousie community and their collective history in this shared geographic and cultural region.

“It’s a lofty project,” says Syliboy, who reached out to Austin, a long-time collaborator, about putting together a proposal for the project in 2017 after Dal put out a call for submissions.

“It took a lot of thought before we reached a decision about whether we should try it,” he says.

Once they saw the potential impact, Syliboy and Austin jumped headlong into the project.

A middle portion of the Staff.

More than 30 materials and 20 processes were used in the creation of the New Dawn Staff and the accompanying ‘cradle’ in which it rests on stage. Where possible, materials of Nova Scotian or regional origin were used, as were found and repurposed elements. White ash serves as the base material for the pole, with driftwood from the Cobequid Bay anchoring the top portion of the staff. Textiles from around the world, recycled gold, and several other natural materials were incorporated throughout using processes ranging from wood turning and textile wrapping to laser cutting, wire weaving, and gilding.

When the New Dawn Staff is viewed up close, you can see how the layers of story and identity mix together to form the whole — similar in many ways to both Nova Scotia and Dalhousie itself.

A village of people, layers of meaning

To achieve such a rich and meaningful result, Austin and Syliboy drew from various communities across the province to find artistic talent and compatible vision needed imbue authenticity throughout.

“The two artists went on to establish a village of creative people,” says Dykhuis.

Wendi Poitras, an African Nova Scotian artist whose family has been in the province for eight generations, contributed several adaptations of Adinkra symbols of Ghana and other places in West Africa to the Staff. Her version of a Sankofa symbol, centrally placed, emphasizes the importance of moving forward while reaching back to learn lessons from the past and to get what has been taken or lost through exclusion, oppression, or neglect.

“This concept is central to understanding and respecting our heritages in this place,” says Austin.

A band of rawhide in knots over birch bark and reed located lower on the staff symbolizes the exchange of knowledge and welcome shown by Mi’kmaq to the French explorers and settlers, who were first accompanied by interpreter Mathieu da Costa, the first African known to land in North America.

Conflict between the British and alliances of Indigenous Peoples and Acadians are symbolized through flags, bayonets, and a portrait of expulsion in a lower section, while at the Staff’s quill band, history is given new life with a modern touch: when a smartphone is brushed near the Staff, a near-field technology chip embedded underneath opens the 1752 Peace and Friendship Treaty on the web.

Descendants of early European and international settlers, Acadians, peoples of African descent, persons with disabilities, all genders and the LGBTQ2S+ communities are all acknowledged with Staff elements in an effort to convey inclusion, diversity, and equity.

“The key for us was to be inclusive, and we really did our best at trying to achieve that,” says Syliboy. “I think we have, starting with the four colours and four directions.”

Higher on the staff, a decoupaged reproduction of “Identities” by Arjun Lal, a Halifax-born artist, acknowledges our culture’s growing awareness of different identities, while braille for the words “I belong” is embedded in both English and French into the Staff’s wood above and below Lal’s piece, following earlier script of the phrase in Arabic, Dutch, and Chinese.

Pre-existing works from many unknown makers are also incorporated into the Staff for their cultural significance, including textiles from around the world (Nova Scotian tartan, Jordanian keffiyeh material, indigo and Bogolan mudcloth from Mali, Nigerian batik, and Chinese brocade), and salvaged leather and buckle from a World War Two era military backpack that’s used as a strap when carrying the staff.

Dalhousie, an unfinished story

The New Dawn Staff replaces the university mace, first carried in academic procession in May 1950. Designed by Dr. Richard Lorraine de C.H. Saunders and carved in oak by A.H. MacMillan with silver and enamel enrichments, the mace was intended to represent maritime traditions and the historical significance of Dalhousie’s service to the Atlantic provinces.

The New Dawn Staff pays tribute to its predecessor by incorporating some elements of the mace (the shamrock, thistle, English rose), but it does so alongside symbols of Mi’kmaq, African and other heritages.

The New Dawn Staff pays tribute to its predecessor by incorporating some elements of the mace (the shamrock, thistle, English rose), but it does so alongside symbols of Mi’kmaq, African and other heritages.

“Recognizing diverse cultures that create this place, whether Dalhousie or Nova Scotia, is not about displacement; it’s about an expanding the narrative,” explains Austin.

Another distinctive quality of the New Dawn Staff is that there is room in various spots along its length for future additions — a humble recognition that Dalhousie’s story is still being written.

For instance, near the top there are 13 gilded wire weavings done by Lily Volio, one for each university Faculty, made up of diverse strands representing faculty, students, support staff and administration. Set snugly into blackened driftwood, there’s room for more bands should new faculties be created. A compartment in the top of the driftwood, concealed by a carving of a mountain emblematic of graduate achievement, houses a scroll. The scroll currently features a poem by Austin, but the chamber’s contents can be changed over time.

“Hopefully this Staff will become significant through its lore and use,” says Austin. “It’s not sacred or a symbol of authority. It’s a walking stick and sometimes things will break. Change them, repair them — make it organic and living.”

A staff for a journey

While a symbol of a scroll on a lower section of the pole emblazoned with the year “1818” gives an early nod to Dalhousie’s founding, it’s this area closer to the top that really represents the university and the student experience.

On the front side, a globe carved directly from the shaft of ash wood is supported by hands holding a symbol of equality — an aspirational symbol that gives way a notch higher to four pillars based on the iconic columns of Dal’s Henry Hicks Building. The start of the driftwood segment (all in Dal’s black and gold colours) features fiddleheads made of curled wire, representing students and other as they begin their educational journey. Passing through the Faculties, represented by the 13 wire weavings, they emerge into a laurel wreath of blossomed ferns representing collective and individual achievement.

At the apex of the staff is the rising sun, 3D printed at Dal’s Product Design & Development Centre with hard resin and gilded by Austin. Inspired by Dal’s 200th anniversary logo, the eye-catching feature connects back to the sun motif at the base as a final reference to the Mi’kmaq — also known as the People of the Dawn, given Mi’kma’ki’s location in the east where the sun first hits in North America.

“I hope it embodies aspirations of the Dalhousie community for a new dawn of both knowledge and understanding,” says Austin of the Staff. “I want them to be able to look at it and say, ‘This is a fitting symbol of a place and time we shared.’”

Syliboy and Austin with the New Dawn Staff.