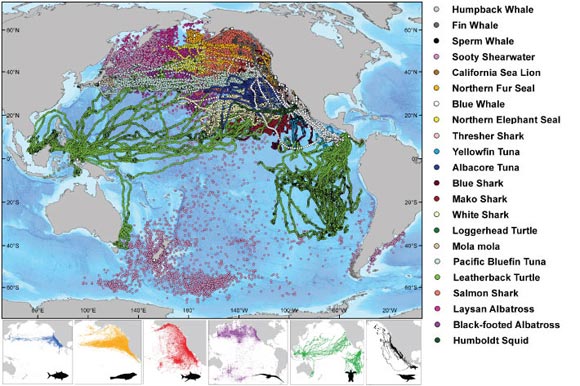

On a map of the Pacific Ocean, the migratory routes of marine species including the humpback whale, the mako shark, loggerhead turtle and northern fur seal look like a heaping plate of multicolored spaghetti. (See map below.)

Leatherback turtles, for example, loop from Indonesia across the ocean to the California coast. Sooty shearwaters, moreover, travel from breeding grounds in New Zealand all the way to the west coast of North America, to Russia and then to Chile. They claim the longest animal migration ever recorded electronically.

“We wanted to be able to build a story on behalf of these marine predators,” says Ian Jonsen, a research associate and adjunct professor with the Department of Biology at Dalhousie University whose two-year study has just been published in the journal Nature.

Where are they going?

The study, co-authored with Barbara Block at Stanford University, summarized the results from a 10-year tagging program called the Tagging of Pacific Predators (TOPP). The TOPP program deployed 4,306 tags on 23 species in the North Pacific Ocean resulting in data that covers 265,386 days—an extraordinary scale by industry standards. Both TOPP and FMAP were projects under the recently concluded Census of Marine Life program.

“Tagging allows us to answer questions like, ‘where are they going?’, ‘how long are they there for?’ and ‘how long does it take them to get there?’” says Dr. Jonsen. “By tracking the movements of marine predators, we can build a map of the important ‘traffic routes’ in the ocean, something we haven’t been able to do until now.”

TOPP scientists have been tagging marine predators for 10 years. Species like sharks, whales, tuna, seals and marine turtles are caught, tagged with an electronic device that keeps track of the animals’ location, and released back into their natural habitat. Their movements are then monitored by researchers at several institutions in California. Dr. Jonsen helped synthesize that data over the last two years right here at Dalhousie.

The study reveals two key corridors, well travelled for species like tunas, sharks, salmon and sea turtles. Two such corridors are the California Current, flowing south from British Columbia along the U.S. coast, and the North Pacfic Transition Zone, connecting the western and eastern Pacific and a watery highway for salmon, sharks, elephant seals and more.

The data collected also indicates these species are quite predictable in their movements and time their migrations so they arrive in the California Current when it is most productive. Species, such as tunas and sharks residing in the California Current, migrate north and south seasonally within this region as it warms and cools.

Like clockwork

The study also indicates that predators, like the leatherback turtle, travel back and forth from Indonesia and Monterey Bay, California each year like clockwork.

Dr. Jonsen believes that although there is still a lot more work left to be done on predicting the movements of marine predators, this study is a step in the right direction.

“Knowing where and when species overlap is important information that can be used to manage and protect these large predators and their ecosystems from human activities.”

SEE: Tracking apex marine predator movements in a dynamic ocean in Nature