|

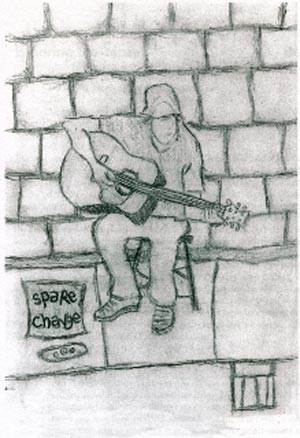

| One of the pencil sketches in Leaving the Streets. |

Pencil sketches of street life show its harshness: the loneliness of soliciting and the monotony of begging.

Just hold that thought and turn the page of Leaving the Streets by Jeff Karabanow, Alexa Carson, Phillip Clement and Katie Crane.

Next the artist reflects a street youth’s musical talent, playing guitar while panhandling. Expressive poetry reveals the emotional reactions of street youth to their world.

It’s a powerful tribute to the creativity resident in a population that is often overlooked. It’s the street seen through the eyes of the youth who live there, rather than impressions imposed by others who are removed from this day-to-day reality.

“The notion of creativity equals survival. This is how to build resilience and coping and it’s how we propel ourselves to different places,” says Dr. Karabanow, professor with Dalhousie’s School of Social Work.

Leaving the Streets (Fernwood Publishing) is the result of a participatory, community-based project covering six regions across the country. Research assistants worked on the streets interviewing youth who were in various stages of exiting street life. Service providers were consulted about their direct observations.

“We want to understand the issues and the role of civil society in this process of exiting because there are difficult layers,” says Dr. Karabanow. “To say ‘good-bye’ to support systems that held your hand—through overdoses, being kicked out of places, after breakups, while panning—that builds tight bonds.”

At the heart of a major transition is a profound act of imagination. That’s the first step to moving away from street life. It’s necessary to visualize a different identity, being in a different place spatially and emotionally.

Dr. Karabanow describes existing mainstream systems as a patchwork offering services such as detox, group counseling, housing issues or help with leases and landlords.

|

| Jeff Karabanow is a professor of social work at Dalhousie. (Danny Abriel Photo) |

Places like the Out of the Cold Emergency Shelter, which opened for the winter season this week in Halifax, focus on a harm reduction model and offer alternatives when other traditional shelters are not able to serve the street population. While Dr. Karabanow believes in this undertaking, he also see it as a band-aid solution.

“The emergency system plays a role, it is the first venue to go to be safe. It is an immediate resort and often when other organizations are full. But now, even the Out of the Cold shelter is often full,” he says. “We need to have a better approach.”

In French, there’s a notion of ‘entourre’ which roughly translates as easing into a new existence by enwrapping and supporting.

Mental health issues and addictions are serious concerns for street youth. While detox programs are available, it is unusual to gain access at the moment that someone realizes they’re ready. Unfortunately, they’ll end up staying on the streets for another week or month.

The research found that having a supportive friend during this process is enormously helpful and, in fact, life changing.

“If you have someone dedicated to helping you, who will let you make mistakes, who will hold your hand until you get into a seven or 12-day detox program, and who will be there when you walk out of the program saying ‘what am I going to do now? it makes a difference,” he says.

By the time someone is accepted as a resident at Halifax’s Phoenix House, or similar counterparts across the country, it’s really the beginning of another phase. With greater stability and privacy, there’s more time to think about next steps. There’s the opportunity to build new routines. Hopefully, with a few weeks under the same roof, supportive new friendships will form. Social workers are also available at transition homes.

“Now the concept becomes acting as an advocate or a broker on behalf of a young person who is moving into a new environment,” he says.

The need is to learn skills, including how to pay bills, find second-hand furniture, reconnect with relatives or friends, return to school or find some work.

“All these tasks are really hard. You don’t do it for them, you’re facilitating. It’s the same role that a good family provides, sharing your fears, helping you to fill out forms, making a doctor’s appointment, all those basic skills.”

“It’s hard to fit into new places,” he says. “All the organizations we work with are phenomenal surrogate families.”

What does success look like? For a young person, success is moving away from the street culture, lining up stable housing, getting started with a training program or finding work, and achieving spiritual and emotional growth.

While it is less often discussed, society benefits too. “The economic benefits are evident, a healthier population doesn’t overwhelm services,” he says.

Nothing endures but change One must desire something to be alive Change your thoughts and change your world So much has changed. I have changed so much, I didn’t even notice. It happened so slowly, so softly. Everything just flowed despite the obstacles. But I always make it! I don’t want to settle for nothing that I know isn’t the best. I saw Joe (whom) I met when I was seventeen when I lived on the street, (and) I had nothing but good to tell him. I am starting to appreciate and respect my life, because I have worked very hard for it. My success can belong to no one else. Dream to believe. * Pixie is a pseudonym used in Leaving the Streets for a member of the research team and a former street youth. Her commentaries and poems are used to illuminate the study. |