|

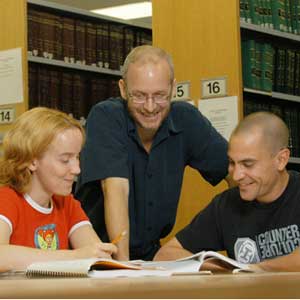

| Prof. Stephen Coughlan believes in a hands-on approach to teaching the law. |

Professor Stephen Coughlan is an award-winning teacher at Dalhousie, who has taught at Dalhousie Law School since 1992. He teaches Criminal Law, mentors students for Moot competitions, and has also taught at the Dalhousie Legal Aid Clinic.

He is the recipient of the Association of Atlantic Universities Distinguished Teacher Award that recognizes a sustained record of excellence in teaching by faculty members from across the Atlantic region.

In the following interview, Professor Coughlan discusses teaching, criminal law, scholarship and his approach in the classroom.

What do you enjoy most about teaching?

The most fun aspect of teaching for me is the interaction with students, especially at the Law School. Virtually all the students come in having another university degree and with a wide range of experience, so they are interesting and intelligent. I am introducing them to a subject that they don't know anything about but that they are able to bring their background to it and discuss it intelligently.

The conversations I have with them are the best part of the job. There are implicit or explicit policy decisions being made in any aspect of the law and they are almost always potentially controversial policy decisions. The controversy isn't always the same from year to year, so it's always different and always enjoyable.

What do you think students take away from your courses?

In criminal law, I try to develop the idea that they are not simply learning a bunch of facts. Criminal law is a method; they are learning how to do criminal law. So I aim to equip them with the tools to analyze further problems as they encounter them. Ideally it should also give them some insight into the underlying policy. In most areas of law, the body of knowledge is constantly changing. In one of my classes, between the time we set the exam and when we finished marking, the Supreme Court of Canada had handed down a decision, changing the right analysis. You can't treat the law as a body of knowledge because some of what we teach them in first year won't be correct by the time they graduate. The students have to know not only what individual cases stand for, but also what future ones stand for as well.

Why do you think your approach to teaching is effective in your discipline?

My preference is for a hands on and interactive approach and that fits well with the notion that we're learning to do things. A lot of the sessions that I have are focused around activities that presume they've read the materials. We're using the information that was in the case readings rather than simply establishing what that information is. If you are trying to have everyone engaging with the material, it's become theirs, they've internalized it. You don't get everybody doing that, but a higher percentage of them do.

How do you integrate your scholarship into your teaching?

I find it very helpful to be the editor of a journal that comes out every three weeks, reporting the latest criminal law decisions. It's very useful in deciding a good new case to discuss in class that presents a different situation or an interesting exam problem. So the research and the teaching overlap perfectly. But it isn't purely just what this decision or that decision says, it's also considering the way the law ought to be developing or whether the direction in which the case law is going is desirable or undesirable. This ties into what I was saying about underlying policy decisions that are made by the law.

What is the most difficult challenge you've faced as a teacher?

Probably the most difficult thing to negotiate in law relates to the different backgrounds and attitudes that students come to the school with and the fact that we are dealing with controversial issues. It is fair to say that our law has been very much shaped by the fact that men were the decision makers for the first 100 years of our criminal law. There are decisions which reflect those attitudes and decisions that are a conscious rejection of those attitudes.

The challenge is that on the one hand you want to give people who don't have that traditional voice an arena in which they feel comfortable expressing their views. At the same time, if the people who are arch-Conservatives on issues don't feel entitled to engage in the discussion and they just feel they are required to write down on their exam the very liberal viewpoint that is being expressed in class, then there is really no chance of them being persuaded because they are not listening, other than to know what to write down on the exam. Whereas if they feel they can actually be part of the discussion they might get persuaded.

Can you describe a unique activity or assignment you have designed for your class and how it well it worked in your class?

I always have a lot of fun with the bookcase. We will have spent six weeks reading cases that set out various rules to do with the mental states accused people have to possess to be guilty of offences. The cases, developed over at least 50 years, are all over the map and as you read one case it's hard to reconcile it with another case. We've read so many cases that are exceptions to the basic rules that it becomes very easy to forget the basic rules.

I have a little stepped bookcase that's four levels high and we spend some time in class just labelling the shelves at various levels of fault. Then I have a bunch of small toys that are all labelled to represent particular crimes. The students come and put the toy on what they think is the right shelf.

We work out when it would or wouldn't be possible to move things between shelves, how the different shelves relate to one another, why the Crown is going to make particular arguments about whether this is a crime or a regulatory offence - students see it dramatically in front of them, it's visual and right there in front of them.

Why do you think this exercise works so well, better than others you have tried?

The interactivity of it - it's a visual representation that goes straight into their brain. I don't think that there's a year that I've done this that somebody hasn't said "can you put that bookcase at the front of the room during the exam." There is something about seeing it that is useful to people as well as the tactile experience. But it's also giving them the framework - it's not about learning about a bunch of facts, it's learning about how to do it.

What advice about teaching would you give to new faculty or teaching assistants?

Two simple things that I would say are, first, teach something you actually care about and are enthusiastic about and if you can't do this, do your best to become enthusiastic about what you teach. I think it makes a major impact for students to know that you find this interesting. I think they will believe it is interesting if for no other reason than it's obvious that you're interested.

Second, this is so basic and so practical but, learn everybody's name. Do your best to learn everyone's name, call on people by name. And don't be afraid to admit that you don't know their name. I think this is important because they get the sense that they are a part of what's going on. It sends the message that you care that each of them is personally engaged; that their presence matters to you.

I don't know, maybe I'm wrong about this, but I also personally think that if you are seen to be admitting that you don't know people's names at a point when you ought to know their names, students feel more comfortable asking the questions that they may be embarrassed to ask. I harbour the hope that if they see you admitting you don't know something you should know that they will feel more comfortable admitting they don't know something they think they should know.

What accomplishment are you most proud of as a teacher?

The thing that I find most rewarding and most fun about teaching is when students get to the stage that they feel comfortable telling you that you are wrong and they are right. By the time people graduate from law school they are now well-informed about the law. So even in your own area of expertise they may have gone off and done some research and they just convince you that the way you are thinking about an issue is not correct. They are comfortable and willing to engage with you as an equal.

Suzanne Le-May Sheffield is the Associate Director (Programs), Centre for Learning and Teaching (CLT), Dalhousie University. The CLT works in partnership with academic units, faculty members, and graduate students to enhance the practice and scholarship of learning and teaching at Dalhousie University. CLT takes an evidence-based approach to advocating for effective learning and teaching practices, curriculum planning, services to support the use of technology in education, and institutional policies and infrastructure to enhance the Dalhousie learning environment. For more information on workshops and programming, please visit http://learningandteaching.dal.ca/

If you would like to nominate an instructor to appear in this series, please contact:

Suzanne Le-May Sheffield at suzannes@dal.ca or call 494-1894.