THE SNAPSHOT

Through a research partnership with Calian, Dalhousie is helping defence and government leaders understand how everyday digital activity creates exploitable cyber risk, and how to mitigate it before it becomes an operational vulnerability.

THE CHALLENGE: Where geopolitics meets the morning coffee

Kevin de Snayer jokes that he does not get invited to many parties. When your professional life is devoted to anticipating everything that can go wrong when governments and large organizations fail to protect their digital systems, you tend not to make easy small talk.

De Snayer is vice president of IT and cyber solutions for defence and space at Calian, a Canadian company based in Ottawa that provides mission-critical solutions for defence, space, health care, and other critical infrastructure sectors. His work often sits at the uneasy intersection of technology and geopolitics: helping clients understand where their systems are exposed, how adversaries might exploit those weaknesses, and what it takes to harden digital infrastructure against threats that are growing not only more frequent, but more subtle.

Data from the Internet of Things and other devices travels unchecked.

“It’s funny,” he says. “At parties, people ask what I do. But after I explain it for a few minutes, they say, ‘You’re not getting invited back. You’re bringing us all down.’”

He delivers this with a wry smile, but he is quick to underline the seriousness beneath the joke. The more connected the world becomes, he says, the more fragile it gets. Systems designed for efficiency, interoperability, and speed inevitably produce what cybersecurity specialists call “digital exhaust”, vast streams of incidental data can reveal patterns of behaviour, relationships, and points of access to those who know how to collect and interpret them.

Much of that exhaust is generated in moments we would not normally associate with risk – before we even log on for the day.

Shown at right: Kevin De Snayer, vice president of IT and cyber solutions for defence and space, Calian.

The internet-connected coffeepot triggered remotely in the kitchen. The Alexa speaker listening to your first words of the day. A phone scrolling through morning headlines while tethered to a home network. A car syncing music from that same device on the commute, its GPS quietly tracking the route. A text sent to remind a child to bring their lunch. Each action emits a signal that can be interesting on its own or cumulatively revealing once combined, cross-referenced, and analyzed alongside the surge of surrounding digital traffic.

Now imagine that digital trail belongs not to a civilian office worker, but to someone employed by the military or a national defence organization. Even junior personnel – an administrative assistant, a private, a contractor – contribute fragments to a larger data portrait that, when aggregated, can hold real strategic value for an adversary.

can hold real strategic value for an adversary.

What troubles de Snayer most is not simply that this data exists, but that the ways it is emitted, tracked, gathered, synthesized, and ultimately exploited remain only partially understood. He spends much of his time in boardrooms briefing senior leaders on the risks but says the single most effective way to focus attention is proof – clear evidence that these exposures are not hypothetical, but already in play.

THE SOLUTION: Turning background noise into evidence

The need for proof is what led de Snayer to Dalhousie University.

For more than two decades, Dalhousie computer scientist Dr. Nur Zincir-Heywood has worked at the frontlines of cyber resilience, studying how networks fail, how attackers operate, and how systems can be designed to continue functioning even when under attack. Her research has long focused on what happens in the background of digital systems – the data that flow quietly, often unnoticed, as networks go about their ordinary business.

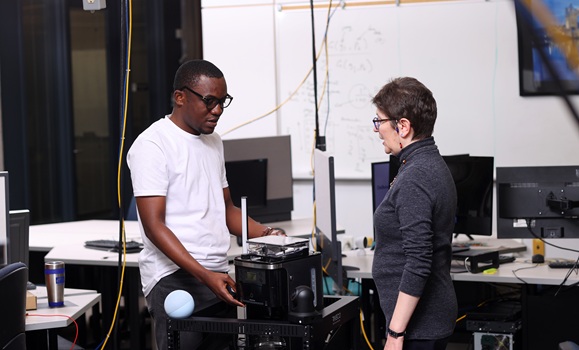

Dalhousie computer scientist Dr. Nur Zincir-Heywood in her lab with a PhD student. (Danny Abriel photos)

“Attackers in the cyber world are not stupid,” Dr. Zincir-Heywood says. “They know how they will be identified or noticed, so they try to be as silent as possible, as passive as possible, until the issue really happens.”

That silence is where digital exhaust becomes critical. Attackers who avoid crashing systems or triggering alarms do not disappear, they blend in. Their footprints are embedded in the same streams of data used for personalization, optimization, and convenience.

The partnership between Dalhousie and Calian, supported through a combination of Industrial and Technological Benefits commitments, federal NSERC research funding, and Mitacs grants set out to make that invisible activity visible. Rather than chasing dramatic breaches after the fact, the work focuses on understanding what data is being produced by our connected environments, where it goes and who might be lurking between the ones and zeros.

THE WORK: The Scandinavian school board that wasn’t

As Dal and Calian’s research partnership has progressed, it has surface surprising patterns that even the seasoned experts did not expect. Data that was intended to go to manufacturers was being siphoned off to destinations in North Korea, Belarus, China, and Russia.

The research unfolds methodically. First comes identification, mapping the devices operating inside a network, from phones and wearables to appliances and building systems. Then comes interpretation, distinguishing between normal operational traffic, data collected for convenience or personalization, and signals that suggest passive surveillance or compromise.

De Snayer describes a case where data flowing from a household appeared to terminate not at a commercial server or cloud provider, but at an IP address registered to a school board in Scandinavia. He says it was a moment that underscored both the complexity and the opacity of modern digital systems.

“Maybe it’s an accident, maybe it’s an old IP, or maybe it’s a big risk, because there’s now a ‘school board’ that’s not a school board, right? Maybe it’s a bad actor that’s cloning school boards. The research is exposing us to different risks that we were not one hundred per cent aware of.”

Dr. Zincir-Heywood says the work is deliberately dual-use. The same techniques that help consumers understand how their data is being used can be applied, with greater urgency, to defence and government contexts. In those settings, every device can become a vulnerability – not by design, but by circumstance. How and when are personnel using connected consumer devices and what information is being transmitting and to whom?

THE IMPACT: Clarity to keep moving

For de Snayer, this is where the research becomes operational. “Through all that research, we are now able to put a report in front of somebody and say, ‘By the way, here we are in a meeting, and everybody’s got their phones turned on and nobody’s got an air gap, and here’s the bad part of that.’”

The desired result is not panic, but clarity.

Rather than urging organizations to disconnect – a practical impossibility – de Snayer says the work helps leaders understand degrees of risk and to make informed decisions about acceptable exposure. “This isn’t about shutting everything off,” he says. “It’s about understanding how difficult an attack is, what information it could yield, and what mitigations actually make a difference.”

This clarity is shaping how Calian supports government and defence clients, from tabletop exercises that allow clients to model vulnerabilities to advisory work in sensitive operational environments, including naval vessels and critical infrastructure. The research provides a new perspective – one that helps decision-makers gain an expanded understanding of how digital systems behave as integrated, living networks where consumer products need to be considered.

Dr. Zincir-Heywood

For Dr. Zincir-Heywood, the broader significance lies in resilience. “There is nothing we can make one hundred per cent secure,” she says. “As soon as you are connected to the internet, assume you are open to attack. The question is can you detect it, can you contain it, and can you keep operating.”