Black Blog

Check out the latest Black Blog post!

Systemic Anti-Black Barriers to Blood Donation in Canada… Part 2

This blog was first posted on the #GotBlood2Give /DuSangÀDonner Black Queer & Trans Blood Blog in English and French

June 8, 2023

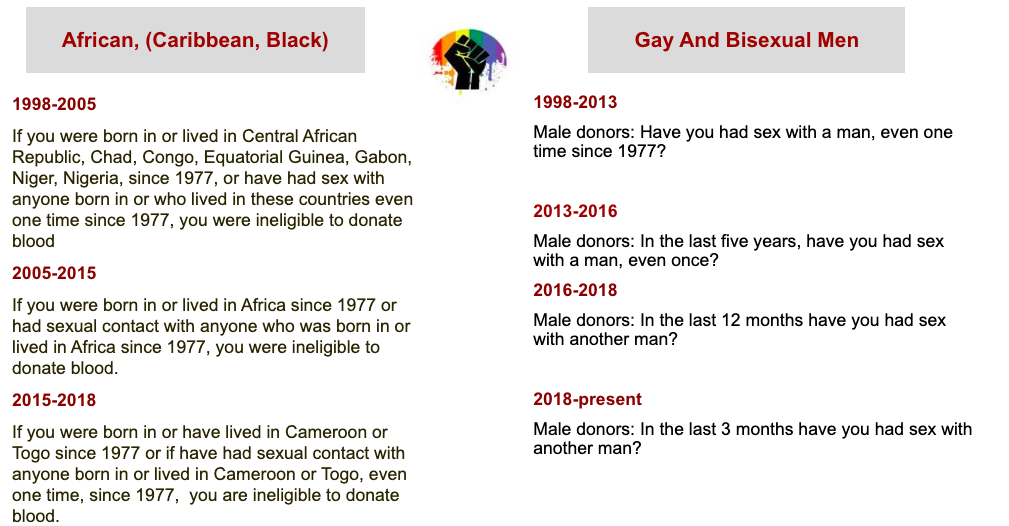

1998: Anti-Black racism, questionable scientific evidence, and blood protocols at Canadian Blood Services.

In 1998, in response to the tainted blood scandal, the federal government created the Canadian Blood Services (CBS), a not-for-profit, charitable organization responsible for the regulatory frameworks related to collecting, managing, and distributing blood products. CBS is also responsible for the surveillance an monitoring of all aspects of the blood system — arguably, CBS should be able to respond quickly if another blood-borne disease should ever threaten the public.

Recommended in the Krever Commission report, and to fulfill its commitment in providing a clean and healthy blood supply, CBS developed and implemented a new donor questionnaire as part of the larger screening process. And so, with the establishment of CBS, the creation of the ideal blood donor became an earnest endeavour. But there already existed established perception that the only way to protect the blood supply was through the cultivation of white heterosexual donors. And this perception found its way into the new organization.

A quick summary of the racialized and anti-Black discriminatory practices in blood donation in Canada, earlier blood donation practices focused on not-white people in general (1940), and Haitian people in particular (from 1983 to 1990). In 1998, this focus changed to Africa.

Canadian Blood Services’ donor questionnaire houses a complex set of ideas that produce the parameters in which we imagine the ideal blood donor. Below is a brief outline of questions included in the donor questionnaire, and the dubious justifications used to support their application.

The donor questionnaire solicits information about and provides direction on how to select for the ideal blood donor. Yet the discourses embedded in the donor questionnaire are also connected with networks of power.

Between the years 1998 (the inception of Canadian Blood Services) and 2005 (at which point the donor questionnaire was amended – see above image) the following questions (former question 30) were asked on the donor questionnaire:

- Were you born in or have you lived in any of the countries listed here since 1977: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Niger, Nigeria?

- Have you had sexual contact with a male, even one time since 1977, who was from Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Niger, Nigeria?

- When traveling to any of the above countries since 1977, have you received blood or treatment with a product made from blood?

The following is amended from my book chapter, “It’s In Us to Give: Black Life and the Racial Profiling of Blood Donation” in Until we are Free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada (2020), with some additions and clarifications.

At this time, Canadian Blood Services argued that this type of “geographic deferral” was necessary since people who lived in these countries may have been exposed to a new strain of the virus, HIV-I, group O, and as such would not be eligible to donate blood. While CBS argued that these questions were “not based on race or ethnicity but possible exposure to HIV-I Group O” the application of this question was decidedly systemically racist. And CBS had (and has) a duty of care to think and act more critically and specifically in the application of the donor questionnaire.

For example, HIV-I, group O was also present in predominately white countries, including France, Belgium, Spain, Germany, and the United States, an yet these countries were not included in the “geographic deferral.” It would seem then, if this strain was beyond testing capabilities of the day, all countries (geographies) where the strain was present would be included in the ban. In other words, the questions would read instead:

- Were you born in or have you lived in any of the countries listed here since 1977: Belgium, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, France, Gabon, Germany, Spain, Niger, Nigeria, and the United States?

- Have you had sexual contact with a male, even one time since 1977, who was from Belgium, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, France, Gabon, Germany, Spain, Niger, Nigeria, and the United States?

- When traveling to any of the above countries (Belgium, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, France, Gabon, Germany, Spain, Niger, Nigeria, and the United States) since 1977, have you received blood or treatment with a product made from blood?

Instead, in 2005, Canadian Blood Services amended the questions to read:

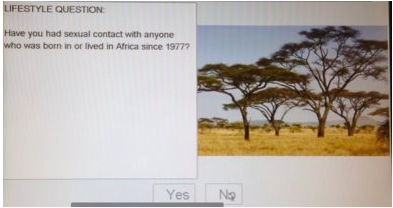

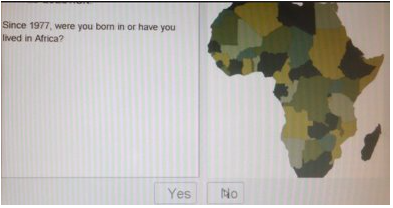

- Were you born in or have you lived in Africa since 1977?

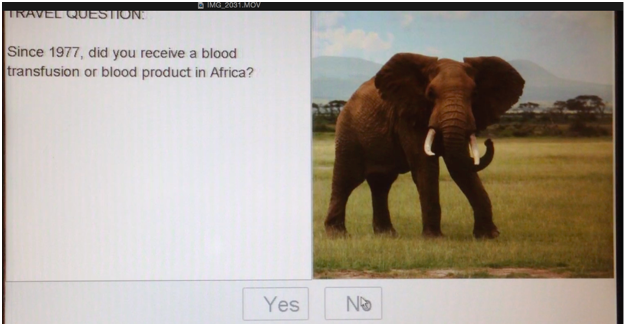

- Since 1977, did you receive a blood transfusion or blood product in Africa?

- Have you had sexual contact with anyone who was born in or lived in Africa since 1977?

The shift from including eight countries in Africa to including all fifty-four countries also demonstrates how anti-Black racism informs the construction of the donor questionnaire.

I have spoken internationally about my research. As a result, white people have shared with me that they also have been barred from giving blood. And yet, white people have also shared with me that, even though they were born in Africa, they were instructed by the Canadian Blood Services’ employees to answer “no” to this question. This is just one example of how these questions are not about geography; the questions are operationalized based on anti-African/anti-Black racist stereotypes.

In 2013, Canadian Blood Services moved to an electronic donor questionnaire, uploading the questions to an interactive computer screen. Not only were the questions now voiced, but generic pictures of African landscapes also accompanied the questions.

Inclusion of images added in the donor questionnaire are presumably used to augment an understanding of the questions.

However, the pictures are eerily reminiscent of the imagery described in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and other earlier affectations of tropical medicine. Yet these images demonstrate and reveal more about the belief of Africa and Black/African people then it does anything to do with potential blood donors. For the blood agency, and those individuals responsible for choosing these images, it conveys that for them Africa is a place of negation, something (or someplace) that is remote and vaguely familiar. And it also suggests that for them, Black people exist within that space of negation – over determined by images of vegetation that stand in for people. The inclusions of stereotypical representations of African landscapes — acacia trees and elephants —help perpetuate the stereotype that disease in Africa is considered natural. These are the kinds of images that facilitate Black people being “scienced into degradation” (McKittrick, p. 117, June 2010). A belief in objective and colourblind scientific discourse and research results in (re)producing scientific racism. This is the very type of “unconscious bias” (in fact it is an example of systemic anti-Black racism and Afro-phobia) that presents itself in blood donor protocols.

CBS relied on these images to communicate and deliver messages about risky behaviour and sources of tainted blood, and in doing so, perpetuated harmful stereotypes about Black people, Black 2SLGBTQIA folks, and Blackness. These stereotypes both simultaneously exceed the limits of science, whilst also engaging in the domain of scientific racism.

The questions changed again in 2015, this time with a focus on Cameroon and Togo – a change that continued to rely on the racist belief that HIV was decidedly an African virus and if there were any new strains of HIV, these new strains could only come from within Africa. To be clear, this is faulty and anti-Black logic.

In May 2018, CBS finally removed questions focussing on Africa. What remains is the lifetime ban on anyone who has malaria, manufacturing a stipulation that would effectively exclude certain populations while appearing on the surface as an innocuous inquiry. Again, this question is not a reflection of current science or best practices in blood collection across the globe. The impact of anti-Black racism remains.

CBS has refused to acknowledge the ways that anti-Black racism continues to inform how the safety of blood is determined. The agency has not taken any steps to repair or reconcile with Black communities in Canada and continues to attempt to erase this history of racism. Removing questions and erasing images does not diminish their anti-Blackness, but their silence regarding racism works to preserve and continue it. A long history of the degradation of Black people and their blood continues.

This is not perceived racism (as some would like to claim) — this is real and operationalized anti-Black racism in the blood system in Canada which precedes but remains upheld by Canadian Blood Services.

Concluding thoughts:

Black communities are disproportionately impacted by the shortage of blood and blood diversity. Sickle cell disease is prevalent amongst Black communities; however, it is very important not to conflate sickle cell as a genetically ‘Black’ disease. Human beings share nearly all their DNA in common and the vast majority of genetic variation occurs within, not across, human populations that might be socially called a race. A shortage of donors in general restricts access and only serves to diminish the supply. Therefore, to have appropriate access to the diversity of blood products, there must also be a diversity of donors.

To build generational donors amongst Black people in Canada, an anti-racist donor protocol must be instituted.

The federal government’s historic Call to Action (January 2021) and acknowledgment by Prime Minister Trudeau that “systemic racism exists in all institutions,” includes Health Canada, Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec.

To practice anti-racism, one needs to begin with steps:

- Publicly name and acknowledge structural white supremacy, anti-Black racism, specifically systemic anti-Black racism (anti-Black homophobia/transphobia) in the agency and donor protocols;

- Investigate how structural white supremacy and systemic anti-Black racism (anti-Black homophobia/transphobia) are specifically operating within CBS and HQ, and operationalized by staff, and;

- Organize, strategize, and commit to disrupt anti-Black racism and put into place an anti-racism strategy that specifically addresses anti-Blackness in the agency and the blood system.

It is my radical hope that Health Canada, Canadian Blood Services, Héma-Québec will undergo public accountability for this continued systemic and structural anti-Black racism (anti-Black homophobia/transphobia) and make appropriate amends. Simply identifying systemic racism without specifically identifying systemic anti-Black racism is woefully inadequate. Black lives matter – in blood donation and as donors. Systemic anti-Black racism with the donor system in Canada has had a detrimental effect. Therefore, Black people, including Black 2SLGBTQIA folks, deserve a meaningful apology. And if there is to be a sustainable uptake of blood donation in Black communities within this country, these agencies must specifically outline how anti-Black racism will be addressed in donor systems moving forward. Perhaps this will only begin with new leadership.

Good news – my work directly led to the removal of former question 30 (the Africa questions). And I am thankful. However, the need to address systemic and structural anti-Black racism in blood donation remains (including addressing the screening question regarding malaria.)

For further information, check out #GotBlood2Give website, Twitter and Facebook pages.