Eva Holland

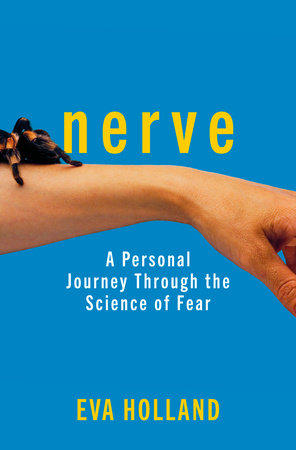

Eva Holland is a Dalhousie/King’s alumna who graduated with an honours BA in History in 2005 and has since gone on to establish herself as a freelance journalist based in Whitehorse. Her first book, Nerve: A Personal Journey Through the Science of Fear, was published with Penguin Random House Canada on April 7, 2020 and was one of Wired Magazine’s “Must-Read Books for Spring.” She talked with Dal MA student Melissa Glass earlier this summer about how she has utilized her history experience throughout her writing career.

Eva “really felt at home” in the Dalhousie History Department and fondly remembers her professors and classmates. Her honours research was supervised by Dr. Chris Bell and focused on the British Empire, particularly Churchill’s relationship with India. Eva had initially planned to pursue a career in academia, and so she completed an MA from Durham University, UK in 2006. But it was there that she realized that her true calling was in writing narrative non-fiction for a popular audience. In her words: “I decided not to do a PhD and decided that if I wanted to be a writer what I should do is try to be a writer.”

After moving back to Canada, Eva worked for a while as an “historian for hire” for a private consultancy firm in Ottawa, doing research largely for land-claim litigation and residential school claims, while writing pieces for newspapers and magazines part time. This job taught Eva the importance of the historians’ Golden Rule: “always be nice to the reference archivist!” Eva became a full-time freelance writer in 2008 and hasn’t looked back since. Her writing has appeared in Outside Magazine, Wired, Canadian Geographic, Longreads, Esquire, and many other places, often focusing on the Canadian North, outdoor adventures, and personal essays.

MG: Did you always have a gut instinct that writing was the thing that you really wanted to do?

EH: I wanted to be a writer since I was a little kid in this abstract way, and I didn’t really know about stuff besides fiction. It was a slow process of discovering narrative non-fiction, the type of writing I do now. I never felt quite right doing academic writing, but I never felt artistic enough to be a fully creative writer, and this journalistic narrative non-fiction, happy-medium ended up feeling just right to me. I was only discovering that type of literature through undergrad and into grad school and then had this lightbulb moment in grad school: “maybe I should just write true stories.”

MG: Has your historical training been helpful for your freelance writing career?

EH: I think the things that were most strange to me were the networking and self-promotion that was required and the running my own business side of things. Those weren’t things that history really prepared me for necessarily – more so, maybe, some of the part-time restaurant industry jobs that I’d had and things like that. But where history did help me a lot, I think, is in organizing information. You know, a lot of working writers don’t have any idea how to navigate an archive or think critically about sourcing – primary and secondary sources and all that stuff. People are often a lot more likely to have a background in English or political science than history, I think, in my field. So I’ve definitely felt like it was useful, and I’ve been able to write some stories that explicitly bring in my historical training.

MG: Is there a historical piece that you’ve written that you’re particularly proud of?

EH: I did a story a few years ago about the internment of the Aleut people during World War II in Alaska [titled “The Forgotten Internment” for Maisonneuve]. They were removed from the Aleutian islands and interned, like Japanese Americans. Except in this case it was theoretically for their protection from the Japanese invasion of Alaska, which a lot of people don’t really know about – it was the only World War II land battle on North American soil… I went and worked in an archive in Anchorage for a week, and I went to the Aleutians and found – I think at that time there were about a dozen survivors left. These camps lacked sanitation, running water, medical care, adequate food, and one in ten people died in the camps… I was able to find four of them who were willing to speak on the record. So that was kind of a perfect marriage of history and journalism for me.

MG: Is there anything that you would do differently in your career if you could go back? Or do you have any advice for students and recent graduates regarding what has served you well in developing a career with your history degree?

EH: I don’t have any regrets. At first I felt kind of silly for doing a master’s degree and then feeling like I was immediately turning my back on it… So I felt a little foolish at the time, like maybe I should’ve figured out my priorities sooner. But ultimately I think that both my degrees, even though they’re theoretically unrelated to what I’m doing for a living now, really, really helped me. They shaped my critical thinking and my research abilities and my abilities to organize information and to express ideas in writing. Yeah, I really value my experience in both programs, and my time at Dal History in particular was just kind of magical. So, I don’t know, I guess my advice would be: don’t let people talk you out of doing a history degree if that’s what you want to do.

MG: Can you tell me a bit about your new book? How has the process of writing and publishing a book been for you?

EH: Nerve is a hybrid of memoir and science reporting. It tells the story of my relationship to fear and my efforts to alter or renegotiate that relationship, alongside a look at psychology and neuroscience and what we know about how fear works in our brains and our bodies and why. So, specifically, it starts with my mom’s sudden death from a stroke in the summer of 2015. For various reasons losing her had always been my biggest fear, but then my worst fear came true and I realized eventually that, although I was really sad, I wasn’t harmed in the ways that I had expected to be. That was sort of empowering, and it made me want to see if I could look at my other fears and maybe face them and overcome them as well, so that was the genesis of the book.

I liked writing a book! I love writing for magazines but writing for a book – it’s more yours and it’s freer in terms of format, you can sort of do what you want. You know, if you want to turn to the camera and address the reader directly you can do that; you can sort of do what you want to an extent with a book in a way that a more structured piece of writing is less flexible… It’s been strange, of course, launching my first book basically three weeks into the lockdown. So, all events, of course, were cancelled, the launch party was cancelled, the book tour was cancelled. But it’s okay, I’ve been doing lots of Zoom and Skype and Instagram Live and Facebook Live, and I’ve had some good media coverage, which has been great. It’s a tough time for everyone right now, and it’s a tough time to be selling a product. But it’s been cool to see how people have stepped up to support authors and bookstores, you know, the things that they value at this time.

MG: While doing your journalism, have people shown a willingness to engage with historical concepts, or is there a disconnect between history as a discipline and what people are thinking and caring about in the real world?

EH: I think it’s both. I think there’s a disconnect and people do care but it’s not top of mind for people. And then when they’re exposed to history they’re so fascinated by it. I’ll give you an example: I did a story for Wired a couple of years ago about how the highest level NICUs [neonatal intensive care units] are changing their approach to treating the tiniest premature babies. It’s for Wired, it’s about new technology, it’s very contemporary, cutting-edge stuff. But I put one or two paragraphs in the story about the history of premies and medical treatments for premies and it was the piece that people responded to the most, because – like so many things in history – it was bananas! The first incubators were funded by having them be like circus attractions. They would have premies in incubators at the world’s fair, they had them on the boardwalk in Coney Island and Atlantic City, and you would pay to see the tiny babies. That’s crazy and readers just loved that detail. So I think that people love history when they’re exposed to it but they don’t think of it as something that they’re interested in… But people in the historical field can overlook what we have to offer to the public, too. It’s so easy when you’re bogged down in this stuff to take it for granted, and then it’s hard to step back and be like “Wait a second – babies on boardwalks?!” And so I think there is a disconnect there, but I don’t think that has to be the case because I think there’s a lot of hunger for this stuff if we can figure out the ways to get it to people.